Don't buy a house

Why the evergreen investment doesn't make sense now

What’s up Graham, it’s guys here :-) If it’s your first time here, hit the subscribe button below to join 40,000+ smart investors and never miss an update on the market again. It only takes a second and is completely free.

For decades, homeownership has been sold as the great American investment. “Buy a house and you’ll build wealth” was practically a cultural mantra. But at today’s prices, that belief risks misleading an entire generation. I know this is going to sound extreme, and maybe I’ll end up being totally wrong, but I need to get it off my chest:

Buying a house no longer makes financial sense for most people.

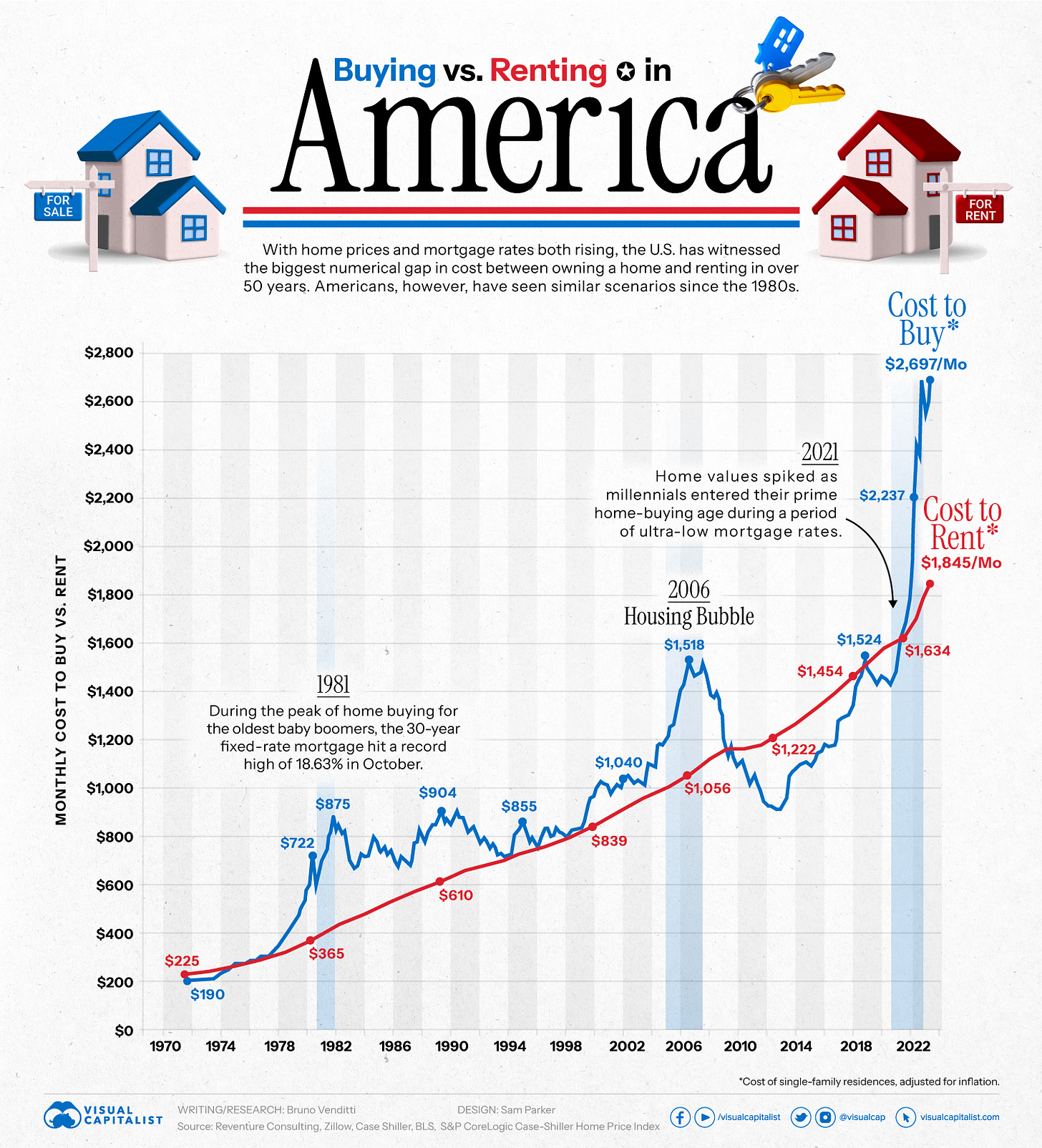

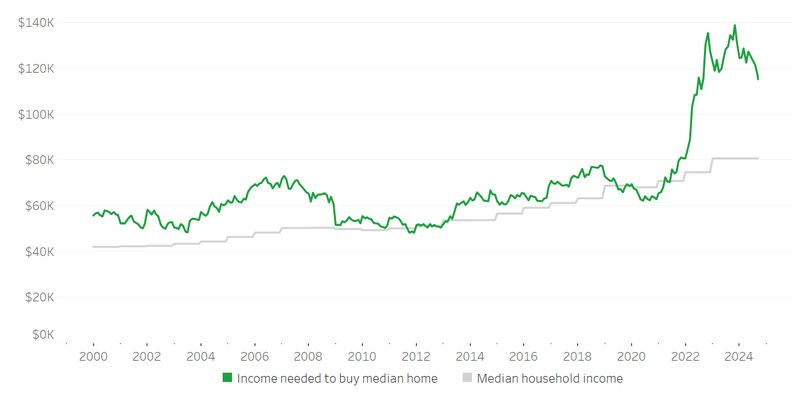

If I bought my same house today, my monthly payment would jump from $5,000 to $16,000. I’m not alone in this. The monthly payment for the typical U.S. home has doubled in just four years, while the income required to afford those payments is at the highest level in history.

Now, there are a lot of arguments against this: real estate prices are still higher year-over-year, rents are getting more expensive, and you can refinance later. And while I say this, I do own a house myself. But I bought mine five years ago at half the price, locked in at a 2.875% mortgage. The math looked entirely different back then, and now, the math just ain’t mathing.

Here are all the reasons you shouldn’t buy a house right now, and the exceptional cases when it does make sense:

From smart choice to deadweight

Buying a home was a smart financial choice, a few years ago. In 2017, I was teaching people how to find deals that gave them instant equity through my videos. By 2020, I was telling people to refinance into lower fixed rates if it saved them money. And for a while, all of this was working. Then 2022 hit.

Suddenly, there was no housing inventory. Homebuilders were delayed from the shutdown, materials were scarce, and the cost of lumber spiked. When a home finally did hit the market, it was bid to a record high because mortgage rates were just 2.75%.

Here’s the math. A $100,000 home at a 5% rate with 20% down costs about $430 a month. That exact same monthly payment could buy you a $130,000 home at 2.75%. Overnight, people could afford 30% more house for the same monthly cost. When people could afford more, prices kept pace as well, and they soared. The catch was that the low mortgage rates weren’t permanent.

Today, rates are at their highest level since the mid-2000s. Inventory is at record lows because homeowners know if they sell and move down the street, their monthly payment doubles. This cycle is only sustainable until one of two things happens: either mortgage rates drop below 4% or housing prices come down. The only question is: which happens first?

The hidden cost of home appreciation

On paper, home values are still rising. National housing values are up 0.3% over the last year. So if you bought a $400,000 home, Zillow now says it’s worth $401,000. You made money, right? Not really.

Here’s what most people do: they see their Zillow estimate trending higher and think, “Wow, my home is already worth $15,000 more than I paid two years ago.” What they don’t add up are the property taxes, mortgage interest, insurance, maintenance, and the opportunity cost of tying up their down payment. Once you run the full math, the picture changes.

Take a median home at $410,000. With 20% down and a 6.2% mortgage:

$19,500 a year in interest

$4,100 in property tax

$2,000 in insurance

$4,000 in maintenance

$100,000 down payment that could have earned 4% elsewhere

That’s $31,600 per year out of pocket to own a house that gained only $1,200 in value.

People will argue that rent is “throwing money away.” And yes, you have to live somewhere. I’m with you on that argument. But is it worth it to commit to a house at the prices they are selling at today compared to rental prices? Today, across all 50 states, buying a home is 50% more expensive than renting. That gap is too big to ignore. Add 6% in closing costs when you sell, and the numbers look even worse.

A real-world example: you spend $30,000 a year on interest, taxes, insurance, and repairs for that $410,000 house. You’d need to sell it for $437,000 just to break even. Even if you own it outright, a 0.3% gain is meaningless when inflation is running at 2.7%. In real terms, you lost purchasing power. At first glance, prices are creeping up. But after adjusting for inflation, they’re falling just like they did in the 1980s.

Why is renting so much cheaper now?

It comes down to distorted supply. You need to understand that there are two types of rentals in the market – the buyers who committed to a house recently, and the ones held down by owners who bought years ago at 3% rates. Because these owners refuse to sell, they recoup their profits by renting at much lower prices and they can undercut today’s buyers. For example:

A $500,000 home bought today costs $3,000 a month with 20% down.

But the neighbor who bought in 2020 for $400,000 with a 3% mortgage pays just $1,765.

They old buyer can rent out their house for $2,000 and make a profit. But the new buyer has to charge $3,000 just to break even.

If you zoom out, you can see this trend everywhere. People with older mortgages can profitably rent for far less than what it costs to buy today. National data shows rents up 3.5–4% year over year. But for new tenants, rents are actually down 8.8%. That tells you where the market is really heading.

And that brings us to the bigger issue:

Housing affordability

This is where things get crazy.

In 2000, the median home price was about $120,000, just 1.7 times household income. By 2024, the median single-family home was $412,000, nearly five times income. That’s one reason homebuyers over 70 now outnumber those under 35.

Subsidies tend to distort markets – and this isn’t the first time this is happening.

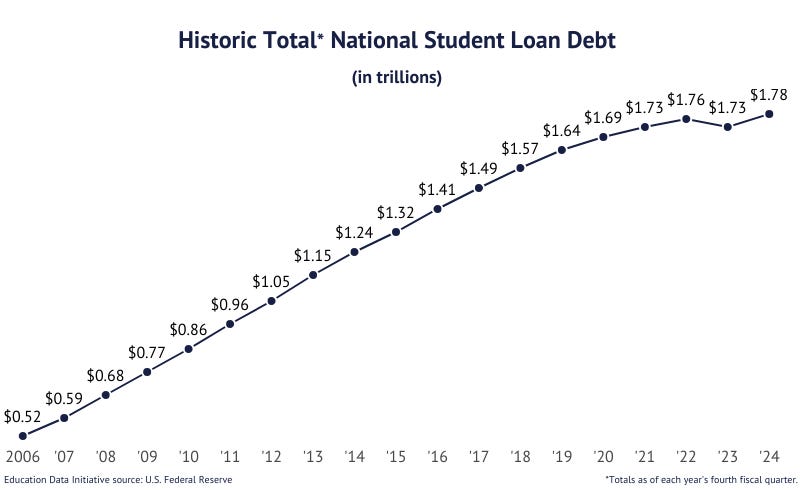

Look at college in the US. When the Department of Education streamlined student loans in the 1980s, the idea was simple. If people could borrow with government backing, more students would get educated and this would grow the economy. But the unintended result was tuition inflation. The more the government guaranteed, the more colleges charged, until we wound up with $1.8 trillion in student loan debt. The cycle became: “How much can students borrow?” followed by “How much can schools charge?”At the same time, graduates’ earnings didn’t keep up. Most colleges now get 60–90% of their revenue from federal money, and a large share of that goes to administrators, not classrooms.

Housing works the same way. Conforming loans are bundled and guaranteed by the federal government. If there’s no private buyer for those loans, the government steps in. That ensures there is always money to buy a house, provided you meet basic criteria like credit score and down payment. The result is higher prices. In the UK, the “Help to Buy” program failed to create more homes but did raise prices beyond the subsidy amount. A U.S. study found homes that qualify for government-backed loans sell for $1.17 more per square foot than identical homes that don’t. In California, a $300 million down payment assistance program was depleted in just 11 days.

To be fair, homeownership does create stability. For many families, paying off a mortgage is their only path to savings. After 30 years, you hopefully own the home outright – that’s why the government supports it and the intention is good. But the road to hell is paved with good intentions. The subsidies create an artificial floor under prices, protecting existing equity at the expense of affordability for new buyers.

Are corporates buying up homes?

Before I get into when buying a house actually makes sense, I’ll address one more concern that I get in comments and mails all the time: “You’re ignoring all the hedge funds and corporations buying up homes!”

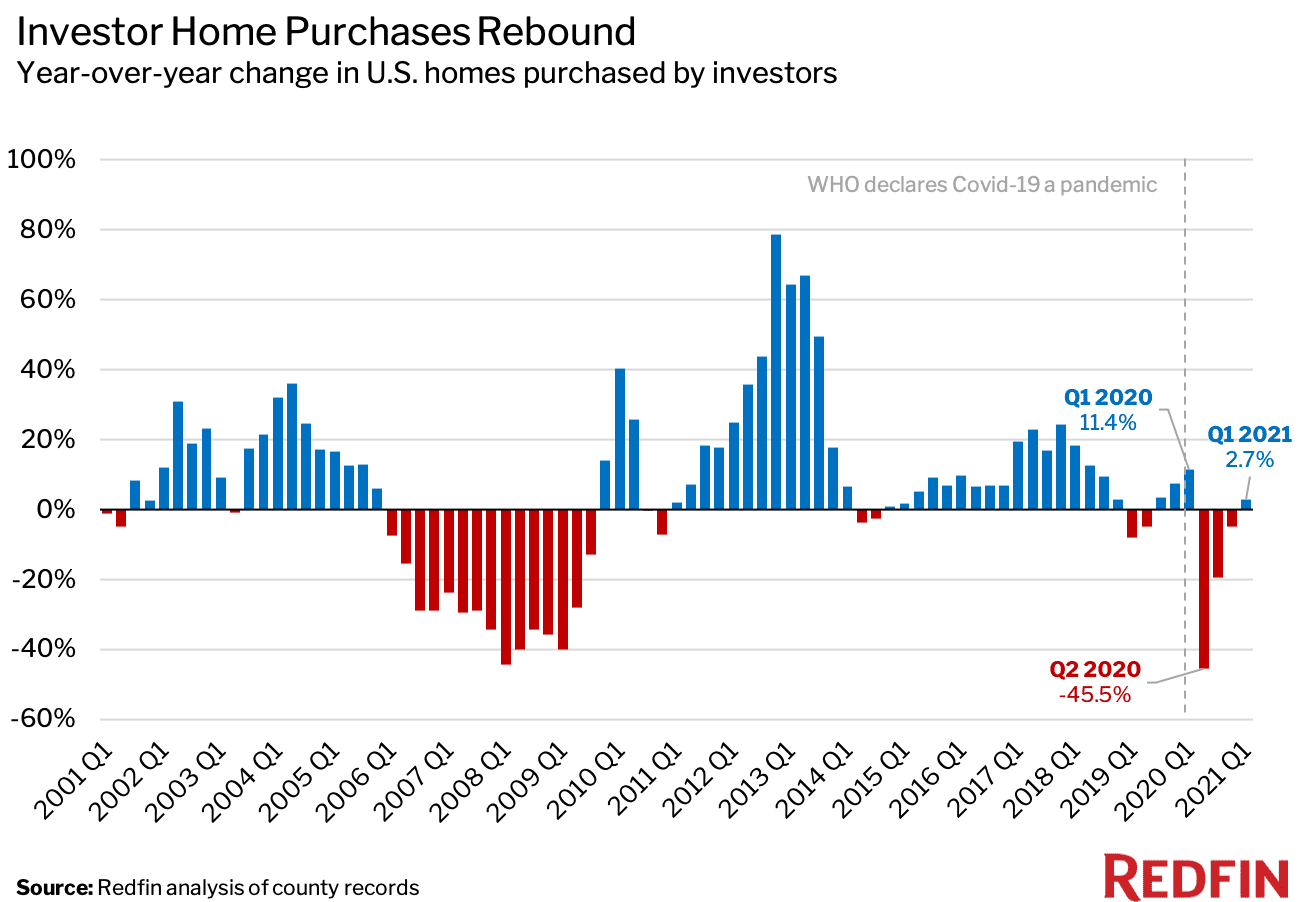

This theory exploded in 2021 when a viral Twitter thread claimed BlackRock was “buying every single-family house they can find, paying 20–50% above asking price, and outbidding normal buyers” (The original thread was deleted. Here’s the archived version).

But the reality is different. The neighborhood mentioned in the thread was a purpose-built rental community developed by D.R. Horton. By the time it was sold, all 124 homes were already leased. The entire package was marketed as a rental-community flip, never intended for individual homebuyers. That’s how Horton walked away with a 50% profit margin. Yes, there are reports that a fifth of California homes are investor-owned. But that figure is actually lower than in 2004, 2005, and 2011, when nearly one in three homes were bought by investors.

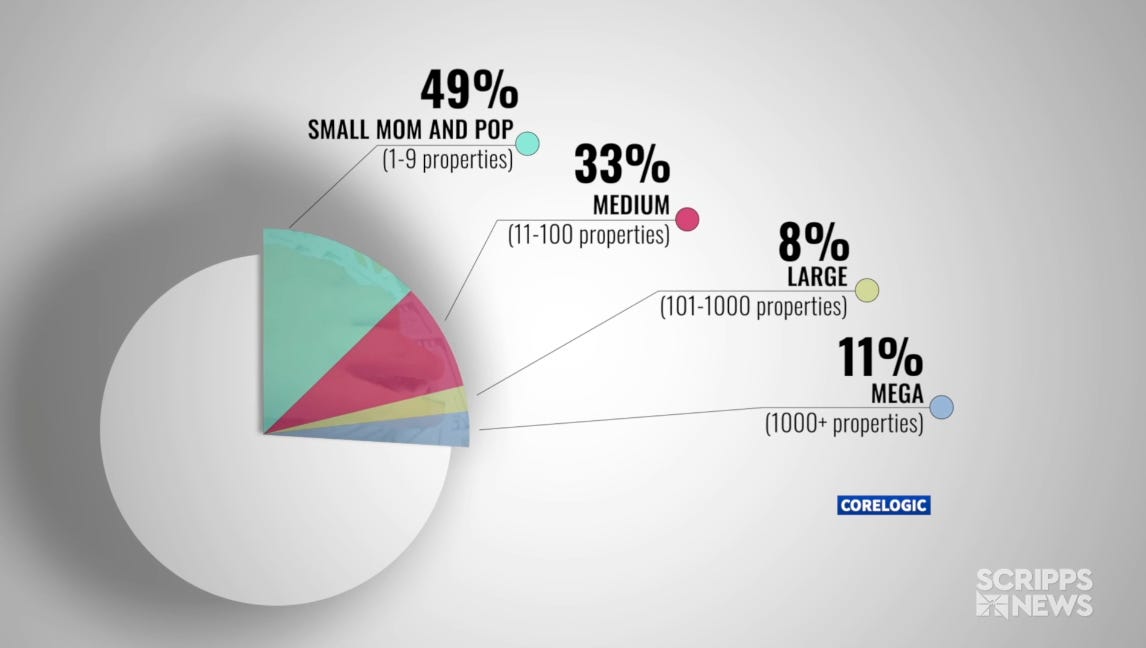

And prices back then were nowhere near today’s levels. It’s also important to clarify what “investor” means. If you buy your first rental property, you too count as an investor – in the same category as a firm buying an entire subdivision. When you break it down:

26% of homes are sold to investors

Half of those are mom-and-pop landlords with fewer than 9 properties

Just 2.8% are owned by corporations with more than 1,000 units

In other words, three-quarters of the time, you’re competing with other families, not BlackRock.

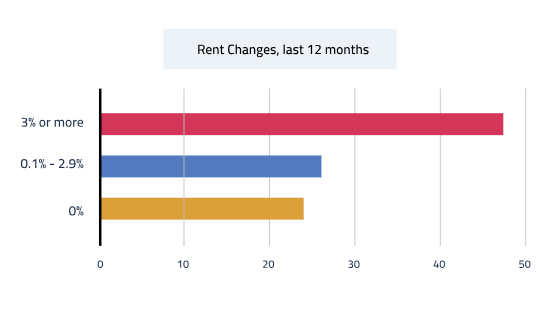

And for big investors, it’s not about being the good guys. It’s just bad business. The math only works when they can buy distressed properties at a discount, rehabilitate them, and rent them out profitably. They don’t want to overpay for the same house a family would buy. In fact, investor purchases are now declining because rents no longer justify today’s high prices. Surveys show that fewer than half of landlords raised rent by more than 3% last year. Many raised it less, or not at all, as the economy cooled.

So no, Wall Street isn’t the main culprit behind unaffordable housing. The real drivers are artificially low interest rates, restrictive zoning, government-subsidized loans, and a culture that still treats homeownership as the ultimate American Dream.

Which brings us to the real question: when is buying a home actually a good financial decision?

When buying makes sense

From my perspective, it comes down to two factors.

First: The emotional side.

There is something satisfying about calling a place your own. You don’t have to worry about a landlord showing up with a 60-day notice. You can remodel when you want. When it’s paid off, you own it outright and can pass it on to your kids. At today’s prices, though, that privilege comes at a premium. With a 6.5% mortgage, 1% in property taxes, and another 1.5% in insurance and maintenance, you’ll spend roughly 9% of the home’s value every year to own instead of rent. That may not beat inflation, but the peace of mind has value that’s hard to measure.

Second: The financial side.

The longer you stay put, the more favorable buying becomes. Historically, the breakeven point was about five years. Today, it might take 15 years or more to break even once you factor in upkeep and the 6% closing costs when you sell. To just test it out, I ran the numbers on a house down the street in Las Vegas where I live. The calculator showed that buying only became cheaper after 28 years! Basically you break even, once the mortgage is fully paid off, assuming both rent and home values rise 3% a year.

Some buyers will argue that lower rates will eventually save the day, through refinancing – and that’s possible. But it’s risky to count on, because those same lower rates could spark another wave of demand that pushes prices higher. On the flip side, as millions of baby boomers gradually leave the housing market, we could see more supply free up by 2035.

The truth is, home prices move very slowly. Think of it like turning a tanker ship: small shifts by one degree add up over years, not months. That’s why, if you are in the market to buy, do it with clear forethought. If you plan to stay long-term, raise a family, and keep the house through thick and thin, then buying makes sense. If you’re comfortable taking the gamble that rates fall later, and you can still afford the payments now, then buying can also make sense.

But if you don’t plan to stay at least 7–10 years, renting is probably the better move. Earlier, you at least had the safety net of renting out a bad purchase. But like I already broke down earlier, houses locked down at low interest rates will undercut you and it’s hard to even break even.

Here’s my bottom line: I don’t think home prices will crash nationwide. But unless mortgage rates come down significantly, renting is the smarter financial choice for most people. Even if the Fed cuts rates, mortgages don’t always follow. They’re tied to long-term bonds and inflation expectations, not just the Fed’s short-term rate. We saw this play out in the early 2000s and again after 2010.

So do the math: Compare renting and buying side by side for your situation. For myself, unless I found a home at 30% off today’s prices, I’d be more likely to rent than buy. And that’s something I never thought I’d say.

If you read this far, let me know what you thought by commenting: Great | Good | Meh | Terrible at the bottom. I read every single comment and email reply.

I’ll see you next week!

One of the best things you can do is to look through the listing history of properties in your area. In my area I'm seeing a trend of houses being listed and delisted multiple times with the price being reduced. At the time the owner may be renting out the home, and those numbers are also going down. The prices seem to be slowly trending back to the mean.

Great analysis as I'm in that decision now considering two homes...one in Carolina's where houses are high and hit your model, the other in Texas where homes are considerably cheaper