Fall of a Giant

What Silicon Valley Bank's failure means for you

What’s up Graham, it’s guys here :-) If it’s your first time here, hit the subscribe button below to join 34,400+ smart investors and never miss an update on the market again. It only takes a second and is completely free.

There’s a theory called the Lindy Effect. If something has been around for a long time, it’s likely that it will continue to exist for a long time. People intuitively seem to understand this, because we have trust in companies and institutions that have stood the test of time. What would you pick to serve at your office party – the soft drink that launched last week, or Coca-Cola? It’s a useful rule-of-thumb.

But sometimes rules fail. Silicon Valley Bank has been around for 40 years, and it’s been the go-to bank for startups. Yet, in the last 36 hours, the bank collapsed in the biggest bank failure since 2008. How did this happen? How did we not see this coming? Ironically, the downfall of the bank might have something to do with how it started.

Silicon Valley Bank was conceived over a game of poker by Bill Biggerstaff and Robert Medearis. The bank’s style was as unusual as the game of poker – it took higher risks by providing banking services to Silicon Valley’s tech startup companies, a market that was not taken seriously by other banks at the time. The bet paid off as tech boomed over the years, and SVB became the “Startups bank”. But the problem with poker is that if you don’t size your bets properly, one round can wipe you out. And that’s what happened with SVB.

Let’s find out what happened at SVB, whether it’s likely to happen with your bank, and what you should do to keep your money safe.

Concentrated bet

Ironically, SVB’s troubles started with a time of prosperity – interest rates had steeply declined since the 80s when the bank started, and the pandemic created a situation that had never been seen before. Clients of the bank were flush with money due to stimulus checks and zero interest rates, and SVB had to take a call on how to invest all those funds deposited with it.

See, here’s the thing about banks: As a customer, you technically have access to your funds at all times, but the chances of all customers showing up for their money together are very small. So banks only maintain a fractional reserve of at least 10% of their funds, and lend the rest of the deposits to debtors who are in need of funds. The interest they earn on this is what the banks profit from. There are regulations on the lending a bank can do, but in this case, the debtor they lent money to was one of the most credit-worthy – The US Government.

Silicon Valley Bank parked $100 Billion of its funds in US Treasuries with a maturity of 3-4 years and locked it in at 1.79% in 2021. The bet in itself was not risky – but the sizing and the timing of the bet was a brash move. By locking in the funds, SVB was betting that the Federal Reserve would hike rates very slowly in the coming months. They got that prediction horribly wrong…

Crisis of confidence

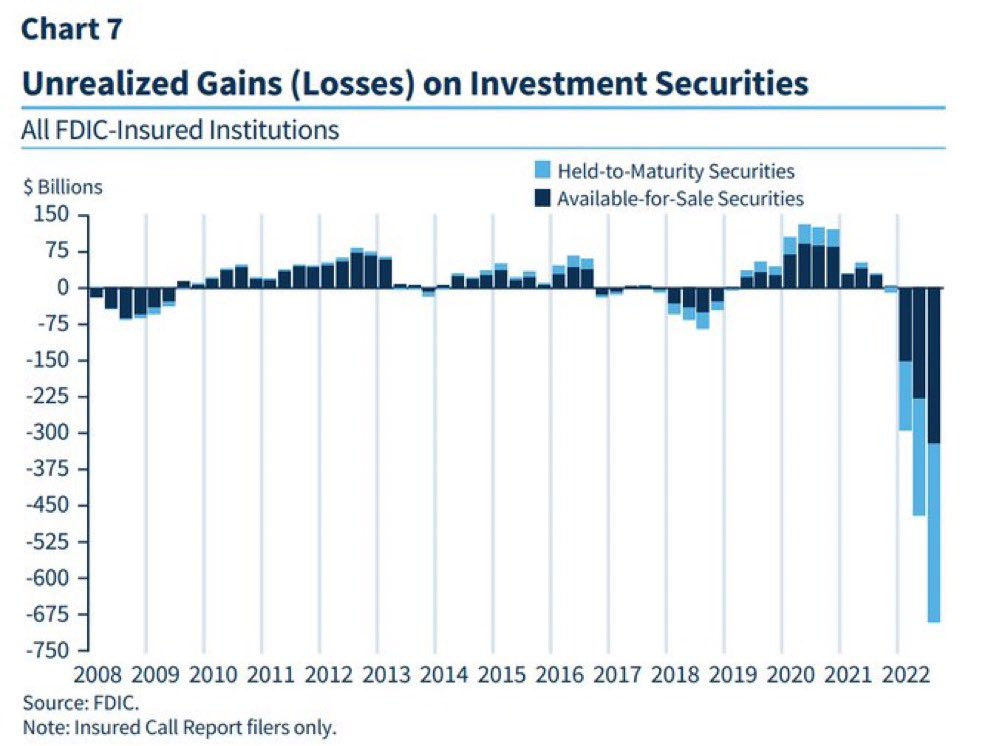

The Fed hiked rates much faster than SVB had anticipated. By locking in their funds at a rate of 2% for 4 years, SVB expected to get $108 on a deposit of $100 for the full term. But rates hiked to 7%, and it meant that by investing $100 at the new rate, they could get $131 over the exact same time. But this also meant that SVB would have to liquidate its old bond portfolio at a loss – when bond yields increase, their value declines, and the original bond would have declined to $77 in value. SVB would have to take a loss if they sold their portfolio. They could have avoided this and still held the bonds to their full term, unless they were pressured to sell and realize the loss.

As luck would have it, this was also a time when customers were withdrawing their money en masse because tech companies were in a slump and had to resort to using their cash reserves. SVB seemed to be running out of money to service the withdrawals, and Moody’s Investors Service threatened to downgrade their credit rating – which would scare depositors. So SVB decided to sell its bond portfolio at a loss of $1.5 Billion… and it scared depositors anyway.

From there, things began to escalate fast. The company announced on March 8 that it would be selling a third of its ownership in an effort to raise $2.25 Billion and offset the bond losses, while continuing to service withdrawals. But word got out that the bank could be facing insolvency, and when the market reopened the next day, the stock price plummeted by 60%.

The chances of raising additional capital became slimmer, and clients started panicking. Peter Thiel even advised companies that were part of his Founders Fund to start pulling their money from the bank. This triggered a full-scale bank run, even while the CEO started calling clients to assure them that their money was safe. You know what they say:

Every banker knows that if he has to prove he is worthy of credit, in fact his credit is gone.

On March 10, Silicon Valley Bank announced that they had failed to raise capital and were looking for a buyer because they had more withdrawal requests than cash on hand. But it was too little, too late. Just hours later, regulators stepped in and closed down the bank with the message:

All of the bank’s deposits have been transferred to the new bank. Insured depositors will have access to their funds by Monday morning. Depositors with funds exceeding insurance caps will get receivership certificates for their uninsured balances.

And that’s why it’s a crisis for Silicon Valley now…

Dummy Insurance

If the funds are insured, there’s no problem – right? Except, there is. The main purpose of FDIC insurance was to provide a safety net for the small guy, and the insurance was capped at $250,000 per bank account. That works fine for individuals, but in this case, the clients of the bank were businesses with balances worth millions of dollars used for working expenses ranging from payroll to overhead to company expenditures – and $250,00 won’t cut it. But what is the extent of the damage?

Here are some quick facts:

Out of SVB’s clients, only 2.7% fall under the FDIC bracket of $250k. The remaining 97.3% had deposits above this limit.

Garry Tan of the Startup Incubator YCombinator said that of the 3000+ companies under their wing, many banked with SVB. More than 400 companies are exposed, and more than 100 cannot make payroll in the next 30 days unless there is a quick resolution.

He also said “This is an extinction level event for startups and will set startups and innovation back by 10 years or more.”

37,000 customers accounted for more than 74% of the bank’s assets, and had an average account size of over $4 million.

The collapse of the bank is sending ripples across the economy – it’s not just clients. Startups like Rippling that used SVB’s technology platforms to process payrolls are also halting operations as their APIs break. Realistically speaking, a startup won’t lose all of its money invested in the bank and will be first in line to receive funds when the bank’s assets are liquidated – but that process could take years, and the question is whether startups can raise enough capital to stay afloat till then. The FDIC will be sending customers a check for $250,000 and a receivership certificate for everything else they owe on Monday, but there’s no timeline after that.

Who are the clients who are being affected by this collapse? Some prominent names are: Roku which holds $487 Million (26% of its cash) in SVB, Sangamo Therapeutics, Ambarella, LendingClub, Oncorus, Eiger, Roblox, Axsome Therapeutics, Protagonist therapeutics, Ginkgo Bio, iRhythm, and Payoneer. There are no doubt countless others. Not all of them will have a fatal exposure, but the effects will be seen only in the coming days. Meanwhile…

Can this happen to your bank?

It’s possible, but it’s very unlikely.

The problem with Silicon Valley Bank is that they had placed concentrated bets on Treasuries and were serviced by Venture Capital funding, which were both hit hard at the same time. I have written earlier about how diversification and asset allocation are what determine the resilience of a portfolio – and while SVB had a dream run when conditions were favorable, they only had to hit one point of failure for the bank to go under.

While there are other banks that have similar kinds of exposure, they tend to be a very small part of the balance sheet, according to the Fed Vice-chair. Even if they experience the same deposit outflows, they are more insulated.

What should you do?

In order to best protect yourself, you should never keep more cash than what’s covered through FDIC insurance, which is typically $250,000, with an individual bank, or up to $1.5 million in what’s called a “Sweep account.” Or you could stick with one of the larger institutions that are not likely to have the same issues.

Another possibility is the use of CDARs (now covered under Intra-Fi) that split deposits of up to $50 million across a network of more than 3,000 banks across the country and let you access the funds through a single bank. But this is a relatively new development and we don’t know if it’ll stand the test of time.

Anyway, if you have large enough sums to worry about, you shouldn’t be keeping a sizeable amount in cash in the first place and should be diversifying your investments, and storing your cash across several accounts in different banks. This is not so easy for businesses to do, but as an individual, it’s something you can easily do to minimize your chances of a black swan event.

We haven’t seen a failure of this magnitude since 2008, and it remains to be seen what happens next: Whether the government deems SVB “Too big to fail” and supports it to prevent systemic collapse affecting thousands of businesses and tens of thousands of employees, or whether SVB will be forced to go through bankruptcy as companies watch the proceedings and wait for their day.

I have mixed feelings on this. It’s terrible that companies that raised and saved up money and carefully prepared for a recession have to go through a crisis like this for no fault of theirs. I find it shocking that a bank could lock away such a huge portion of its assets and essentially place a bet on the Federal Reserve which could break the bank if the bet went wrong. No bank should be allowed to take such a sizeable risk and regulations should be put in place to ensure more diversification.

On the other hand, a limit of $250,000 makes no sense for business accounts – it works great to shore up individuals, but business accounts should have access to much higher limits (maybe with higher premiums) insuring a percentage of the deposits (like 25-50%) instead of a number. When the payroll of thousands of employees is at stake, and failures in payments could ripple across the industry, we need better safety measures for businesses against such unforeseen disasters.

What do you think? Should the FDIC have special measures to insure businesses?

But who knows, maybe Elon Musk will decide to buy SVB with Twitter and turn it into a digital bank – crazier things have happened. Make sure to subscribe and stay tuned, and I will keep bringing you the latest updates as they happen.

Hours of effort and research went into making this ten-minute read. If you found it insightful, please help me out by clicking the like button and sharing this article.

Treasury bills mature in one year or less. SVB owned treasury notes, not treasury bills.

Time for change. Allow banks to have private commercial insurance or reinsurance on their deposits. FDIC charges the same premiums to all banks irregardless of how reckless they are. Insurers can and will charge more for bad management in premiums just like they do in all consumer and business lines. Look at drivers in Massachusetts where all drivers are charged the same. No one cares how bADLY they drive. Safe drivers pay the same as bad drivers. Conservative banks will pay lower premiums and thrive. Bad banks will either reform or go out of business