Why I'm selling all my LA properties

Red tape in the City of Dreams

You don’t have to do it all yourself. Upwork Business Plus helps you buy back your time by connecting you with elite freelancers and AI-powered recruiting that finds the right talent fast.

Focus on growing your business, not juggling every task.

Spend $1,000, get $500 back in Upwork credit. Offer ends 12/31/2025.

Los Angeles is supposed to be the city of dreams.

For a long time, that was true for me. I grew up there, went through the public school system, and did what everyone in LA does: sat in traffic, watched prices climb, and tried not to think too hard about how expensive everything was. But underneath all of that, there was still this feeling that if you worked hard and stuck with it, the city would give you a shot. That is exactly what happened.

Back in 2008, when I was eighteen, I used to walk into open houses I definitely could not afford, just to ask the agents how to get started in real estate. One of those agents became a mentor. Through him, I began earning commissions as a leasing agent. Those leasing clients later turned into buyers, and within a few years, I was making more money than I ever expected.

I took that money and bought my first house for 59,500 dollars. It was about ninety minutes away, owned by the bank, and it needed a lot of work. When I first walked in, it smelled like cat urine. There was so much junk piled up that I later realized there was an entire room I had missed because the doorway was completely blocked. Most people would have walked away, but I saw an opportunity.

I had the place cleaned out and fully renovated: new floors, new kitchen and bathrooms, fresh paint, a solid roof, and a usable yard. Once it was livable, I rented it out. Then I repeated the process with other properties that no one else wanted. In a typical Los Angeles remodel, I would spend anywhere from 50,000 to 200,000 dollars. My philosophy was simple: instead of going for a flip, I could make the home genuinely nice and attract good tenants. This would keep turnover low and let the property slowly pay for itself.

For about ten years, that approach worked really well. Values went up. I locked in low, fixed-rate mortgages. Rents were steady, and my tenants were great. The city had issues, but it still felt like a place where hard work and long-term thinking were rewarded.

That changed in 2020.

If this is your first time here, hit subscribe to join over 39,000 finance-savvy subscribers and receive a mail every Monday that will make you a smarter, wealthier, and happier investor:

The pandemic effect

When the pandemic hit, Los Angeles enacted an eviction moratorium. In practice, if a tenant did not pay rent, you could not evict them. What started as an emergency measure was extended again and again, and the moratorium ended up lasting three years. Even in 2023, it was still considered an “LA health risk” to evict someone who had not paid rent in years, while landlords were still expected to keep paying the mortgage, property taxes, insurance, and repairs.

I was lucky. None of my tenants stopped paying, and my properties kept performing. But the policy itself said a lot about how the city viewed landlords.

There is this idea that landlords are all wealthy people squeezing tenants for profit. In reality, many are just mom-and-pop owners who happen to have a second property. Roughly half of all landlords manage their own units, and about 50 percent originally lived in the home themselves. On average, they make around 10,500 dollars per year in profit, total.

From 2020 onward, LA felt more restrictive and more hostile to private owners. Crime ticked up, and the general direction of the city seemed worse. I eventually moved to Las Vegas, but I held on to my LA rentals because I had great tenants and good long-term financing. I told myself I could live with the policy risk.

All that was true until I tried to do the one thing the city constantly says it wants: add more housing.

The ADU That Broke Me

In January 2025, I started looking at the numbers on building an ADU, or accessory dwelling unit. In my case, the plan was to take an old structure on one of my properties and convert it into a detached two-bedroom, 700 square foot home.

The math looked very compelling: I estimated I could invest about $220,000 to build the ADU. At market rents, the unit would cash flow reasonably well. At the same time, I would be adding badly needed housing supply to a city that constantly talks about a “housing shortage.” Someone would get a clean, new home in a good neighborhood. The property value would go up. The city would collect more in property taxes. Honestly, it felt like a win for everyone involved.

If the project went smoothly, I could repeat the process and build another five units across different properties. So I decided to treat this first ADU as a test.

The Permitting Gauntlet

The first step was getting permits. That took around three months and cost more than 4,000 dollars in fees to the city. Slow and expensive, but not surprising. I just considered it cost of doing business. Once the permits were finally approved, my contractor started work.

By July, the ADU was almost complete. We found a tenant who wanted to move in on September 1st. All we needed was the city to come out for a final inspection, sign off, and issue the certificate of occupancy so the place would be legally habitable.

That is where everything went off the rails.

Inspector Number One

The city inspector came out after a couple of weeks of delays, walked through the unit, and failed us for a missing AC drain line. That part was frustrating, but fine. The rules are the rules.

My contractor told the inspector he could install the drain line right away if there was any chance we could get signed off that same day. The inspector looked at the time. It was a Friday at about 4 PM, right before a long weekend, and he simply said he could not. This was his last inspection of the day, and he would have to come back another time.

We fixed the issue. Then we tried to schedule the same inspector again. Instead, we got bounced around. About a week later, a different inspector showed up.

Inspector Number Two

The new inspector walked the property and gave us a fresh list of items to fix that the first inspector never mentioned. According to my contractor, this is “just how it works.” Each inspector has their own preferences about what they want to see, and when someone new takes over, they will often add a few extra requests.

So we did that. We fixed everything on his list and scheduled another visit. He came back. We were hoping this would finally be the sign-off.

Instead, he told us we now needed a sewer line CCTV inspection before he could pass the ADU. This is a camera that goes through the sewer line to check for any problems, and it had to be done by one of the “approved LA city sewer line inspectors.” That inspection cost another 600 dollars.

Again, this is the kind of thing that could have been requested months earlier, before we had a tenant waiting. Instead, it was added at the very last step.

The Surprise 22,000 Dollar Problem

The camera went through the line. Day-to-day, the unit functioned completely fine. Toilets flushed, water drained, everything worked. But somewhere in the middle of the street, where my sewer line connects to the city’s line, the inspection found an issue. The inspector told us this problem had to be fixed before he would sign off and allow the unit to be rented. That repair, because it was in the street and tied into the city system, was quoted at 22,000 dollars.

At this point, I already had months of delay, a tenant who was supposed to have moved in, and a nearly finished ADU sitting vacant. I asked the inspector if we could get a temporary allowance that would let the tenant move in with a clear guarantee that I would fix the sewer line within the next sixty days.

Then he disappeared.

Radio Silence

The inspector, who was already hard to reach, suddenly became almost impossible to contact. Calls went to voicemail. Messages were not returned. I talked to his manager, who basically suggested that I “try him more often.” We did that. Nothing. When we finally heard back, over a week later, he said the whole situation was now out of his hands. The file had been passed to Public Works, and I would need to get the street repair done before he could come back and issue final approval.

So I moved forward with the 22,000 dollar repair. By now, we were more than a month past the initial inspection, with no rental income coming in and carrying costs adding up. I still believed that once the repair was done, this nightmare would be over.

That is when I hit the moment where I thought, “I am done.”

The 75-Day Notice That Broke Me

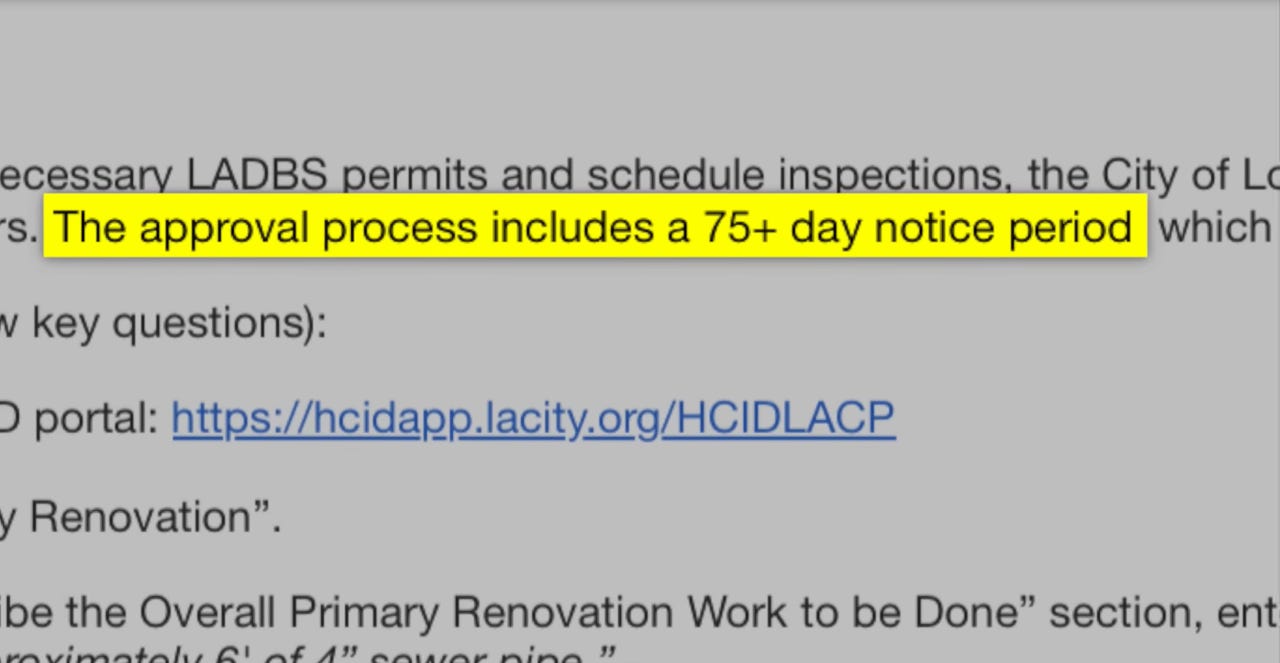

Apparently, the City of Los Angeles would not allow the sewer line work to begin until I gave my existing tenants 75 days advance written notice that their water might be turned off for a few hours in the afternoon while the repair was done. These tenants worked during the day. Practically speaking, the repair would not affect them. We were talking about a short, scheduled interruption, not some multi-day outage. Yet the rule was the rule: no 75-day notice, no work.

To me, it felt like a completely unnecessary waiting period that delayed everything for no real benefit. I pushed back. I asked for an exemption. I explained that I had already invested hundreds of thousands of dollars into this property, had a finished unit waiting, and a tenant who would happily move in. Nothing.

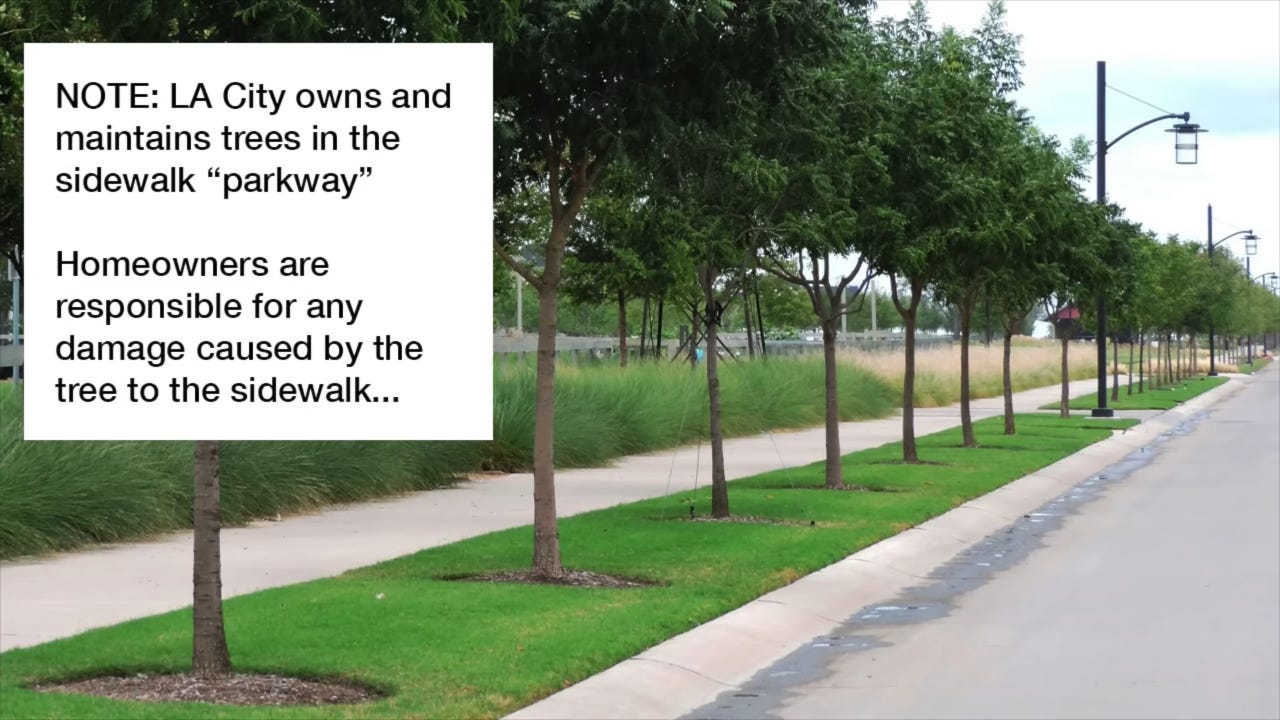

Three weeks go by, and another inspector shows up who says that to do the sewer line work, I also have to fix 22 feet of sidewalk in front of the property that was uneven because the roots of a city-owned tree were intruding. And to fix that, I need to get a root-trimming permit from the urban forestry department.

At this point, it just feels like I’m getting pranked. I have a contractor working tirelessly, a tenant ready to move in, and me who’s ready to do all the work right now. But our calls are going unanswered and going to voicemail, emails are taking weeks for a response, and making an in-person appointment is impossible because everything is booked out weeks in advance.

Eventually, I had to ask myself a simple question: is this worth it?

The answer was no.

Before we move on, if you’ve ever had a similar experience with red tape while trying to build something or do business, drop a comment. The more we talk about this stuff, the more awareness it’ll create:

Why I Am Selling My LA Properties

The ADU experience completely changed how I see Los Angeles as an investor.

On paper, this was exactly the kind of project the city should want. I was taking my own capital, adding a new, clean, well-built unit in an existing neighborhood, raising the property tax base, and helping with the housing shortage. If it went smoothly, I was prepared to do it again and again.

Instead, I ran into a maze of red tape, inconsistent inspections, last-minute requirements, tens of thousands of dollars in surprise work, and months of delay for something as minor as a few hours of water interruption. I am not saying every project in LA is this bad. I am saying this one was bad enough that it changed my risk calculation.

There are now too many restrictions, too much uncertainty, and too much policy risk for me to justify putting new money into that market. It is not just about profit. I have never been the person trying to squeeze every last dollar out of a tenant. I have kept rents stable for good tenants and prefer long-term relationships over turnover. What this is really about is a system that punishes the very people who are willing to add housing and invest in their communities.

A City That Says One Thing And Pays For Another

If the city truly wanted more housing, it would:

Make permitting predictable and transparent

Give inspectors a consistent, clear checklist

Fast-track small projects that add supply in existing neighborhoods

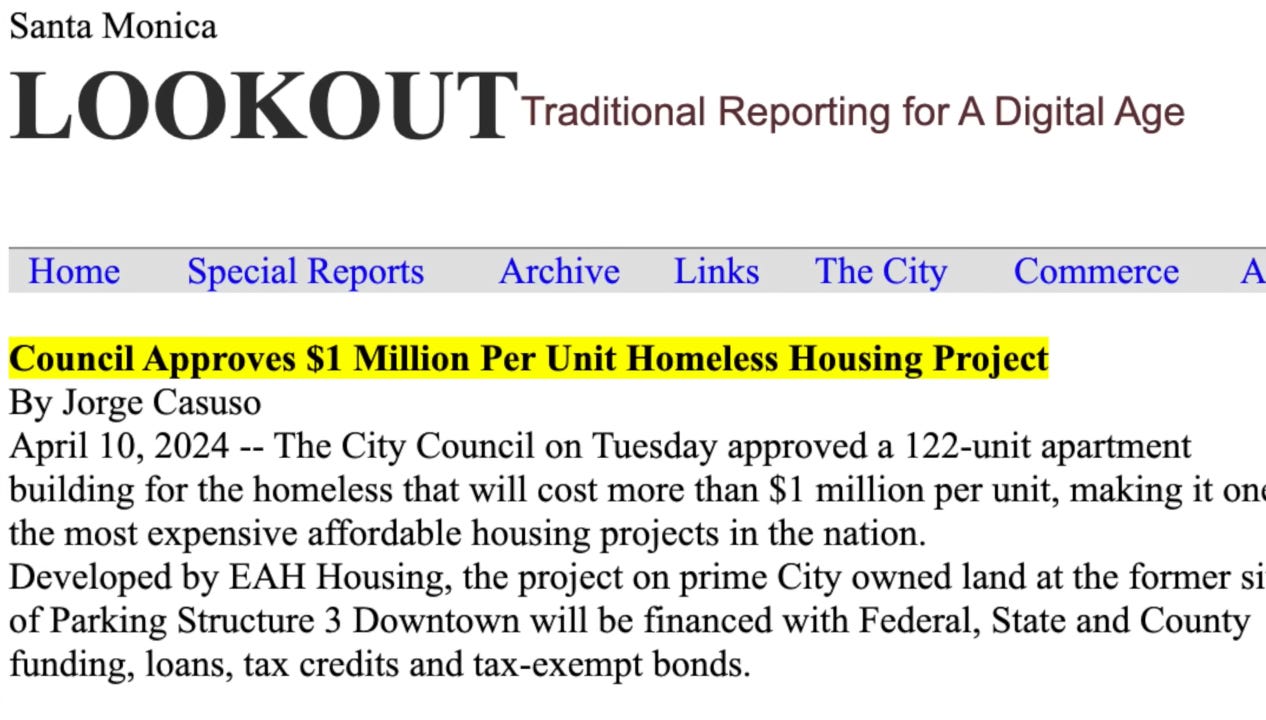

Instead, what we see are headlines about ultra-expensive government-built housing. For example, Santa Monica recently hit about 1 million dollars per unit on one homeless housing project. Another development in Skid Row has been reported at roughly 600,000 dollars per unit.

Landlords are not always popular, and I understand that. But what’s the alternative? Government housing? If a city struggles to handle the permitting for one ADU, how do we expect it to efficiently build and manage tens of thousands of units on its own?

Meanwhile, regular working families are living paycheck to paycheck, and small investors who would happily build and maintain good quality units are being buried under rules, delays, and arbitrary decisions.

This is why I have made the decision to start selling my Los Angeles properties and to stop putting new capital into that market. I do not want my money tied up in a system that treats private development as a problem instead of part of the solution.

If You Are Thinking About Investing In LA

I am not telling you that you should never invest in Los Angeles. There are still great neighborhoods, good tenants, and unique opportunities. But if you do choose to invest there, I think you need to understand that your biggest risk may not be interest rates or vacancy. It may be the city itself.

Here are the lessons I took away from this:

Policy risk is real. An eviction moratorium that lasts three years, or a 75-day notice requirement for a few hours of water shutoff, can completely change the economics of a deal.

Red tape has a real cost. Months of delays, extra inspections, and surprise requirements are not just annoying. They are real money out of your pocket.

Incentives matter. If a city’s regulations and culture make it harder and riskier to build, investors will eventually stop building. That hurts everyone in the long run.

For me, the conclusion is simple. LA is where I started. It is where I learned the business, met my mentors, and built my first portfolio. I am grateful for that. But right now, I would rather put new money into places that actually want private development and make it possible for people like me to add supply without going through a nightmare.

If you are thinking of getting into LA real estate, I am not here to tell you “Do it” or “Don’t do it.” I just want you to see the reality behind the headlines, so you can decide for yourself whether the risk, the red tape, and the uncertainty are worth it.

That’s it for this week! I hope you found this issue useful. It was a hard one to write and come to terms with. If you read this far, please like the post and share it with a friend:

And don’t forget to check out today’s sponsor! I’ll see you next week.

Great video!

Yeah, Graham's recent moves make a lot of sense if you’ve lived through California’s real estate and regulatory gauntlet long enough.

Myself Surviving the ‘90s crash and 2008… and apparently the only way to get a city building department to move is to go full scorched-earth 😂

Back in the day, second bogus inspection and I’d go lawsuit mode:

- Sue the inspector personally

- Sue his boss

- Sue the whole department

- Drop liens on every utility line into my property include them also.

- File prejudgment remedies attachments on their trucks and office furniture also personal properties.

Best part? Getting the inspector’s spouse served at home. Phone rings:

“Why are you suing my husband?!”

Me: “Let me check my calendar and get back to you” 🤣

Only had to do it a couple times. After that, permits and variances sailed through like I was the mayor’s cousin.

New generation: it’s time to have option B to lay the smackdown again. A lot of these inspectors see young investors killing it and get jealous—they wish they had the balls to flip or build wealth like you. So they flex, act like they’re your boss, and red-tag everything just because they can.

Nah. Remind them who actually pays their salary. Some lessons still need to be taught… and re-taught.

The war never ended. 🔥